Getting your code to your friends

Reminiscing about software distribution

For as long as I’ve been interested in software development, I’ve been interested in how software makes it onto a computer. “Works on my machine” was never quite enough… how would it work on someone else’s computer? Here’s a stroll down memory lane, starting from the 90s.

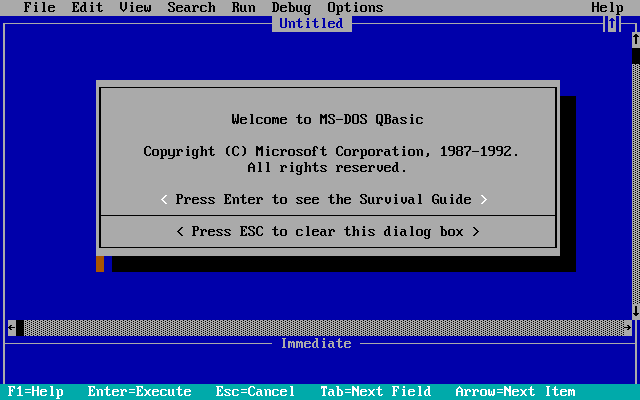

QBasic (early 90s)

In the early 90s, when I was about 8 years old, someone showed me that my computer came with a piece of software called QBasic - it came with the MS-DOS operating system. Although nobody in my family knew how to use it, and this was long before I had access to the internet, it came with an impressive set of examples as well as an interactive reference manual that I recall as being very thorough. Having messed around with it and made a few animations and utilities, I thought it would be cool to give copies to my classmates to play around with; y’know, like a professional software developer would.

The software, as I wrote it, was a collection of source code files - just text

files with a .BAS extension. For anyone to run those programs, they’d have to

open QBasic themselves, select “File→Open”, navigate to my file, then use the

“Run” menu to actually run the program. And presumably figure out how to exit

QBasic when they’re done. Now, 8-year-olds in the 90s were used to computers

being slightly harder to operate, e.g. typing out a command or two to open a

game; indeed, friends did figure this out. But this still felt like a super

janky way to distribute software.

What I actually wanted to do was provide a “self-contained” program, one where

you simply enter its name and it starts up, like any other DOS program I’d seen.

Ideally, it would have the fashionable .EXE extension (the term “EXE file”

seemed pretty much synonymous with “program”).

What I wanted to do was allow people to run LUTZKY1.BAS with one command. This

could’ve been accomplished by adding a file LUTZKY1.BAT (BAT for MS-DOS

Batch, not BAS) with these contents:

| |

I would’ve needed to terminate the program using the SYSTEM command rather

than END. This way, indeed typing LUTZKY1 into the prompt would’ve run my

program and exit normally. However:

- I don’t think I knew how to do that

- It still flashes the QBasic IDE on startup

- I was still relying on QBasic being installed on the destination machine, and I knew (though?) older versions of MS-DOS didn’t include it.

- Having things in multiple files still seemed “off”. I now wonder if I could’ve designed a file to work both as the batch file and as the BASIC file.

I had heard rumor of the “professional, expensive” bit of software I needed - a

compiler, which would perform the right magic to me a shiny, self-contained

LUTZKY1.EXE. But this sounded like an expensive thing to even ask my parents

for, never mind the fact I had no idea where one buys software - the local

shops only seemed to stock games and office productivity software.

For whatever reason, this was important enough to me to try some truly wacky

stuff. I vaguely remember messing around blindly with files on my computer,

trying to generate an EXE file complete with an icon - efforts included taking

something called the “PIF Editor”, which creates shortcuts to files and

ostensibly adds icons to them… and replacing one of the system EXE files

with it, in case the filename was “magical”. The real magic was young me

learning the valuable lesson that I should’ve made a backup of this file before

replacing it.

Visual Basic (late 90s)

By the late 90s, Windows 9x came around along with Microsoft Office, which had a wonderful capability: Visual Basic for Applications. this gave me my first experience writing actual GUI applications, strangely embedded within an Excel spreadsheet. Most memorably, Pokémon was a huge deal at the time, and I had created “APCO - A Pokémon Card Organizer” - a trivial deck building app.

On April 1st, 1997, the very first episode of the Pokémon anime was shown on Israel, on channel 6; I was the official “hero of the day” guest, as a Pokémon expert. I got to this position by nitpicking on some “kids’ portal” website that their Pokémon page contained inaccuracies, which landed me a job as their Pokémon card strategy reviewer; I was 11, so they paid me in Pokémon cards.

For the anime premiere I was interviewed by Dana Dvorin; I have sadly been unable to find any footage of this hilariously awkward interview.

Once again, I wanted to distribute this software - perhaps using this magical

thing I now had access to called The Internet. And, once again, sending an

excel XLS file around with a big “click me to start the actual program button”

seemed, well, janky. Amazingly, a friend had a copy of “really real Visual

Basic” (the coveted compiler I had heard of), and was able to convert my janky

app-in-XLS to a proper shiny EXE file. Slight caveat - there was a runtime

library that had to be distributed alongside it, or it wouldn’t work.

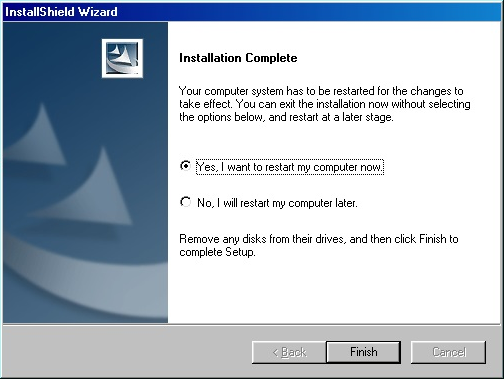

This got me looking at installers. All “serious” software was proudly using

InstallShield (this was before these newfangled .MSI files - even the

installer was a shiny .EXE!), but looking at a trial version left me

scratching my head at how things should be organized. Finally, a self-extracting

RAR file (yay shareware WinRAR) did the trick. I vaguely recall successfully

uploading the finished product to some download site of the era, probably

Tucows.

Linux (early 2000s)

In high school, I was first introduced to Linux. It (Mandrake 8.1) came in 3 CDs burned by a guy who couldn’t have seemed shadier if he had pulled them out of a trench-coat. Regardless, it was enlightening: How can this possibly be legally free? Wait, it just comes with a compiler? What do you mean the compiler doesn’t contain a GUI? It was a fascinating dive into understanding what my computer even is; while I was old enough to remember pre-Windows days, I had switched to Linux from Windows 981, so all of my experience with Windows was as a graphical wrapper running inside DOS. For instance, not having drive letters (A, B nor C) was wild.

I didn’t spend long with Mandrake before switching to Gentoo Linux, where

installing software is accomplished with the emerge command. The emerge

command magically (to me, at the time) gets the software from the internet and

compiles it. In my mind, I was Hackerman. In reality, it

was more often “sorry dad, you can’t use the computer today, a new version of

KDE just came out and the build will take a few hours”. I stuck with Gentoo

until college1, when a stack of remarkably slick-looking envelopes with

Ubuntu CDs showed up. At this point Linux started seeming serious, and the “year

of the linux desktop” meme started to get to me. Ubuntu also killed off

install-fests2, as installing it was too easy to justify getting

friends and pizza together.

My grandma got my old PC with it, so I can proudly say my grandma is a former Gentoo user. She exclusively used the browser, but whenever she needed support I was the only one who could provide it, as any other support people invariably tried to get her to find the “start” menu, even when the problem was entirely within gmail. ↩︎

If anyone has footage of the install-fest I was forced to trick Moshik Afia to go to, as part of פעם בחיים on Yes, please send it my way! ↩︎

As I dove deeper into Linux, I realized I’m seeing some of the older jank once

again. Lots of software came as shell scripts that ran java, meaning you had

to have the Java Runtime Environment installed. Python software came as scripts,

which needed not only Python itself installed, but usually some additional

python libraries. At this point I noticed the following:

- This only seems less janky in Linux because executables usually don’t have

filename extensions; the difference between a “clean

.EXE” and a “janky.BAT” is tucked away in the file contents. - “Proper” C programs also need a bunch of stuff installed along with them.

The Linux ecosystem has a dizzying array of solutions to this problem. From meticulously2 packaging DEB files through FlatPak/Snap/whatever through Docker3. I’m the kind of nerd who’s excitedly following FasterThanLime’s series about how Nix presumably does this better than anything else.

Afterword - the web

At some point, probably too gradually for me to notice, web apps became actual apps. XMLHttpRequest is horribly named, but pretty transformative when used by sites to dynamically fetch more information; Javascript had gradually transformed to “the Assembly language of the web” (i.e. it’s the thing stuff compiles to4); but the really cool thing about web apps remains distribution: Just give people the URL.

Yes, there’s work to do. You need a server, you need to handle its uptime and connectivity (cloud has made this effectively trivial, even more so for quick demos with things like ngrok). The app itself also needs to be written differently: updates are nontrivial, if any state is saved then backwards-compatibility becomes difficult, you need to handle different browsers (and different device types); it’s not easy. But a giant ecosystem has developed around solving these problems, and the infrastructure to use the web has become, by comparison, effectively ubiquitous. And to my 8-year-old self, there’d be nothing cooler than that: “Forget the floppies, just give a note with your address to your classmates; it’s basically guaranteed to work on their computer”.

Windows 2000 had pretty much skipped home PCs around me, and XP was new and untrustworthy. ↩︎

The Debian New Maintainers’ Guide, which explains how to do this, starts off with “social dynamics of Debian” before getting into the details of actually packaging anything. ↩︎

Sometimes described as “It works on your machine? Then we’ll ship your machine.” credit ↩︎

I think compiling stuff to WASM is becoming more popular nowadays. ↩︎